|

| Burying the dead at Wounded Knee. |

Thursday was, among other things, the anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre on Dec. 29, 1890 --- the slaughter of 250-300 Lakota people, men, women and children, on and near Wounded Knee Creek on South Dakota's Pine Ridge reservation.

I'm not about to report upon or analyze Wounded Knee --- that's been done many times, sorted and resorted, and there's plenty of material out there about this sorrowful event. I started many years ago with Dee Brown's 1970 "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," and have kept reading now and then over the years.

But I got to wondering yesterday about how Lucas Countyans learned of the massacre as 1891 dawned more than 130 years ago. And how accurate those first (and later) reports were.

+++

The information source for some would have been daily newspapers. Two dozen or more reporters were in the vicinity of the massacre when it occurred and three at the scene. Their dispatches began to flow via telegram on the 30th and would have reached Chariton when the Des Moines, Ottumwa, Burlington, Omaha --- even Chicago --- newspapers arrived via train later on the day they were published.

But most Lucas Countyans did not have access to daily newspapers and relied on weeklies like The Chariton Democrat that included the following paragraph in its edition of Jan. 1: "A special from Wounded Knee says that on the 29th a battle occurred between the Indians in which fifty soldiers and 120 Indians were killed and wounded."

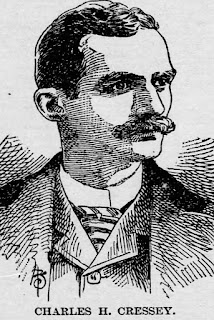

By the next week, The Associated Press had distributed dispatches from Wounded Knee nationwide and more complete reports would be included in Chariton's three weeklies, too, including what probably was the most widely read report nationwide --- written by The Omaha Bee's Charles H. Cressey. It was published in dailies on Dec. 31, 1890, and republished in Chariton's Herald along with later reports on Jan. 8, 1891.

Cressey, 33 at the time, was one of three reporters at Wounded Knee when the massacre occurred. The others were Charles W. Adams of the New York Herald and Thomas H. Tibbles of The Omaha World-Herald. Cressey, native to Cannon City, Minn., had grown up and graduated from high school in Des Moines. (I've utilized material gathered by Samuel L Russell as he prepared for publication his 2016 volume, "Sting of the Bee: A Day-By-Day Account of Wounded Knee And The Sioux Outbreak of 1890--1891 as Recorded in The Omaha Bee," for background material on Cressey)

The Bee was known for its sensationalist reporting and Cressey, a talented writer and aggressive reporter, was a master in that field --- often not allowing the facts to get in the way of a good story. But his reports drew readers and it's been suggested that his dispatches from Wounded Knee and related sites were the most widely read in the United States, helping to shape at the time and for years after how white America perceived the event.

Here is Cressey's original dispatch. No mention of women and children or the very old. Lakota are blamed for instigating the tragedy. The word "massacre," used in dispatches by other reporters at the scene, does not appear. Perceptions are shaped by the way an event is reported rather than by how it actually occurred.

+++

The Omaha Bee's correspondent at the camp on Wounded Knee telegraphs as follows concerning the battle there:

In the morning, as soon as the ordinary military work of the day was done, Maj. Whitside determined upon disarming the Indians at once and at 6 o'clock the camp of Big Foot was surrounded by the Seventh and Taylor's scouts. The Indians were sitting in a half circle. Four Hotchkiss guns were placed upon a hill about 200 yards distant. Every preparation was made, not especially to fight but to show the Indians the futility of resistance. They seemed to recognize this fact, and when Maj. Whitside ordered them to come up 20 at a time and give up their arms, they came, but not with their guns in sight. Of the first twenty but two or three displayed arms. These they gave up sullenly, and observing the futility of that method of procedure, Maj. Whitside ordered a detachment of K and A troops on foot to enter the tepees and search them.

This work had hardly been entered upon when the 120 desperate Indians turned upon the soldiers, who were gathered closely about the tepees, and immediately a storm of firing was poured upon the military. It was as though the order to search had been a signal. The soldiers, not anticipating any such action, had been gathered in closely, and the first firing was terribly disastrous to them. The reply was immediate, however, and in an instant it seemed that the draw in which the Indian camp was set was a sunken Vesuvius. The soldiers, maddened at the sight of their falling comrades, hardly awaited the command, and in a moment the whole front was a sheet of fire, above which the smoke rolled, obscuring the central scene from view. Through this horrible curtain single Indians could be seen at times flying before the fire, but after the first discharge from the carbines of the troopers there were few of them left. They fell on all sides like grain in the course of a scythe.

Indians and soldiers lay together, and the wounded fought on the ground.

Off through the draw toward the bluffs the few remaining warriors fled, turning occasionally to fire, but now evidently caring more for escape than to fight. Only the wounded Indians seemed possessed of the courage of devils. From the ground where they had fallen they continued to fire until their ammunition was gone or until killed by the soldiers. Both sides forgot everything excepting only the loading and discharging of guns.

It was only in the early part of the affray that hand-to-hand fighting was seen. The carbines were clubbed, sabers gleamed, and war clubs circled in the air and came down like thunderbolts. But this was only for a short time. The Indians could not stand that storm from the soldiers. They had not hoped to. It was only a stroke of life before death. The remnant fled, and the battle became a hunt.

It was now that the artillery was called into requisition. Before, the fighting was so close that the guns could not be trained without danger of death to the soldiers. Now, with the Indians flying where they might it was easier to reach them. The Gattling and Hotchkiss guns were trained, and then began a heavy firing, which lasted half an hour, with frequent volleys of musketry and cannon.

It was a war of extermination now with the troopers. It was difficult to restrain the troops. Tactics were almost abandoned. The only tactic was to kill while it could be done. Wherever an Indian could be seen, down to the creek and upon the bare hills, they were followed by artillery and musket fire, and for several minutes the engagement went on until not a live Indian was in sight.

No comments:

Post a Comment