Werner Gertberg, who out of the good of his heart has undertaken a great deal of research into my Redlingshafer family in Nuremberg and elsewhere in Germany, located and shared one of the missing pieces the other day.

This is the 1848 notice that my great-great-great-grandparents, George and Doratha Redlingshafer and their large family, would be permitted to leave their native farming village of Heinersdorf, Bavaria, and emigrate to the United States --- unless someone protested within 14 days.

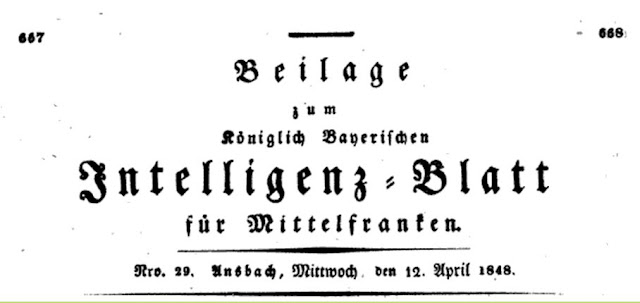

It was published in the Supplement to the Royal Bavarian Intelligenz-Blatt for Central Franconia on Wednesday, April 12, 1848. Since the family did arrive at the port of Baltimore later that year, then travel to southwest Pennsylvania where they lived for a time before many family members moved onward to Iowa, it would appear that no one protested.

George Redlingshafer died at Guttenberg in Clayton County during 1856, but Doratha and four of their eight children --- Anna Margaret (Redlingshafer) Rosa/Wulf, John George Redlingshafer (my great-great-grandfather), George William Redlingshafer and Margaret Anna (Redlingshafer) Hupp --- all settled down and lived out their lives in Benton Township, Lucas County.

The only minor puzzle in the notice is the fact it states that George and Doratha planned to travel with 11 kindern, or children, when they had only eight. Perhaps the three extras were grandchildren, children of John Kaspar Redlingshafer, an older son of George's by his first marriage. We just don't know.

At that time, Bavarians who planned to emigrate needed permission from the royal government to leave the country, but did not need permission to enter or settle in the United States and so the screening process in Baltimore and at other ports would have been minimal.

+++

This all brought to mind the question of language, and some of the accommodations various levels of government, schools and many businesses in the United States now make to ease the way for immigrants for whom English is a new language. For some reason, these accommodations generate anger now and then among those who have forgotten their own immigrant roots and seem to be operating under the delusion that the ability to speak English should descend like a gift of the spirit once one crosses a U.S. border.

It's just never worked that way, and still doesn't.

There's no indication that my great-great-great-grandmother, Doratha, ever learned to speak English. She really didn't need to; always surrounded by family and, until arriving in Lucas County, living in U.S. communities where German was spoken. All of the Redlingshafers were well-educated for their time --- but in German. And learning a new language becomes increasingly difficult as one ages.

The younger generation of immigrants, including my great-great-grandfather, John G., mastered English, but he made the wise decision to marry Isabelle Greer, a school teacher for whom English was native language and she helped him grind away the rough spots.

The third generation --- that of my great-grandparents --- were in some instances bilingual. There are family stories that suggest some of this generation at least could speak among themselves in German when they didn't want their children to understand what they were talking about.

the fourth generation --- my grandparents' generation --- had no ability at all to read, speak or understand German.

+++

In Lucas County, we're lucky to be able to see that dynamic at work among our neighbors with roots in Ukraine. Grandparents most likely never will learn English. Their children will struggle with but eventually master the language. The youngest immigrants will be bilingual. And the fourth and future generations, unless family bonds are held tightly, run the risk of losing the language entirely.

It's the American way.

No comments:

Post a Comment